What could be a better way to start talking about Idea generation than refer to, the possibly apocryphal, great quote attributed to the Commissioner of the U.S. Patent Office in 1899, Charles H. Duell, who said “Everything that can be invented has been invented.” Despite all of our technological breakthroughs, this is far truer today than ever before. All around the world, executives, journalists, consultants, politicians, and influencers bring in various experts even before their new ideas are ready. The problem? This limits them to solving problems in old ways and the effect is bad/no innovation. Let’s take a look at one example.

From idea to commercial proof in 10 weeks – idea generation at the forefront

- Why do we still have spokes on cars? Because horse-drawn carriages needed them and we still think of cars as a horse wagon with a number of horses, wood panels, and spokes.

- Why did we have external antennas on most smart phones long after it was rendered unnecessary due to antenna design and utilized frequencies? Because we saw them as communication equipment and wanted to show off.

- Why do we still employ ROI calculus for deciding the unknown?…You guess!

Biased idea generation leads to higher risk

We are all biased, often leading to worse decisions than those a chimpanzee would make. Indeed, the late Hans Rosing, with whom I had many interesting discussions, received world-wide acclaim for proving not only that medicine students with top grades statistically knew significantly less about global health than did a group of chimpanzees, but also that Nobel prize winners in medicine were merely on par with them. Why? Because the humans suffered from bias. These findings point towards the fact that, when you deal with a new topic, you must explore and learn it in an unbiased way. The more you know, the higher the risk. The more at stake, the higher the risk. But these risks are negatively correlated to self-confidence. In fact, because self-confident people are less interested in risk, they tend to make very dangerous decisions, while thinking the very opposite.

Dreams are the touchstones of creativity

Statistics belie the common misconception that you can transform a eureka moment into a commercial success. Rather, it is the result of thousands of experiments, failures, observations, and inspirations from history and other disciplines, as well as an unbiased creation process which sees thoughts grow step by step. You cannot use traditional probability on a premature idea, simply because probability does not work when uncertainty is high. Moreover, novel things are, by definition, uncertain because they have never been tested before.

Big dreams often grow from the smallest of seeds, invisible to all but the most careful observers. As Bergman wrote, “My films grow like a snowball, very gradually from a single flake of snow. In the end, I often can’t see the original flake that started it all.”

In the film Inception, a crew of corporate dream raiders is pinned down under heavy fire as Joseph Gordon Levitt struggles to imagine his way out of their innovation crisis. Tom Hardy, an expert in the creative subconscious, advises, “You mustn’t be afraid to dream a little bigger, darling.” Provisioned with bigger dreams, the crew finds that its possibilities open up, objections drop away and that its members can move on smoothly to the next phase of their journey.

Christopher Nolan, the writer-director of that movie, was heavily influenced by the master of translating intellectual dreams (and nightmares) to film: Ingmar Bergman. Bergman said that his severe upbringing, mirrored in the film Fanny and Alexander, drove him to deeply explore his dreams while awake. “Hence my difficulty,” he confessed, “in separating the dream world from the real one. I became a great liar to escape the punishments.”

Indeed, dreams are the touchstones of creativity, as they emerge out of emotion-tinged memories, remixed and remastered by the logic circuits of the brain.

Dream Big – Start Small

So, where do you start then? The first step is to formulate a problem statement, something that really would make a difference if you could solve it. Then, you might ask yourself, how do I find that problem? Good question! One very effective way is to map key drivers in order to identify potential scenarios. Key drivers can be mapped out using PESTLED, leading to the identification of key drivers. Thereafter you can start looking for feasible things and simply try them. Also start searching for less feasible things that have a highly probability of high impact, and begin formulating a plan based on 2-5 scenarios that are very different and very promising. These scenarios represent the hunting ground for your problem statements – you must simply ask yourself “What if?”.

Once you have a problem statement, you can start idea generation. However, the most effective path forward is not to seek out experts, as they are usually biased and limited in their problem-solving abilities because of their repsective past experiences. Instead, think like a Hollywood screenwriter, and do not let yourself be limited by reality. Remember, you are going to change reality, but you just do not know exactly how quite yet. One of the most descriptive speeches with a theme of visionary thinking without knowing how to get there is John F. Kennedy’s proclamation that humanity would reach the moon.

“We choose to go to the Moon. We choose to go to the Moon…We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win, and the others, too.”

John F. Kennedy was bold, ready to think outside of the box and move forward towards solutions. In Magnus Penker´s podcast series, Play Bold, the prelude to the book Play Bold – How to Win the Business Game through Creative Destruction, many of the world’s leading experts in their fields give insights into how to start somewhere without knowing where to end.Listening to Professor Emeritus and brain of the year, Leif Edvinsson, and what we can learn from the space race between the former Soviet Union and the U.S.? How can cinnamon increase your innovation capability? Is the world linear or nonlinear? How can we use the Japanese -BA form to figure out the future?

The Process – Ideation Management

When you have identified and formulated a problem statement, preferably a bold one, it is time to start the more controlled part of the process—often called ideation, ideation Management, or idea generation.

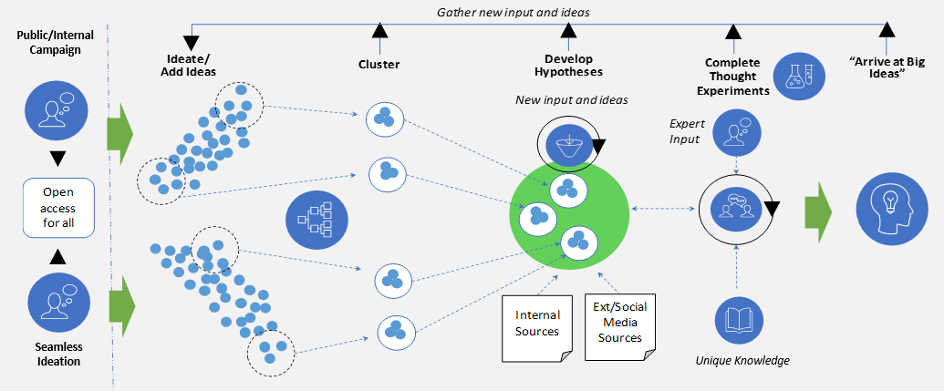

The Innovation360 Ideation Process

This process starts by defining funnels in which insights can be collected. This funnel can be push or pull, meaning that you can ask or that you can observe. Examples of pull funnels are anthropological or ethnographic studies, big data analytics, inadept interviews, desk research, and scouting, while examples of push funnels are ideation campaigns, A and B testing, prototyping, and workshops. Here, it is important to remember Ingmar Bergman: it starts with a seed, and grows. The analytical technique for this concept is clustering, during which you cluster ideas from different funnels, evolving them into big ideas that allow you to formulate hypotheses and start testing them. Through iterations, you are then able to validate, reject, or merge/split big ideas.

Working with a proper ideation platform and well-defined push and pull funnels to feed idea generation typically results in 2 – 5 big ideas per problem statement, including a well-formulated hypothesis. Done in an efficient way, this can be managed in 2 to 4 weeks. However, you must have the right capabilities, leadership, and tools at your disposal.

The Capabilities for Idea Generation

Using InnoSurvey©, the world’s largest database and most comprehensive innovation management assessment tool—with data from +5,000 organizations in 105 countries— Innovation 360 has proven via published, scientifically vetted papers that organizations working with radical innovation are more well-structured in ideation (idea generation + selection) than ones utilizing aspiring incremental innovation (aka, continuous improvements). is the biggest differences include capabilities for cross-functional work, breaking down goals into actions, dealing with uncertainty, learning from failure, and being able to inspire the organization with a higher purpose.

Now, based on thousands of projects and work with executives around the world, combined with our data, we have learned that the most successful leaders are humble and service-oriented. Though they are still bold and demanding, they do not pretend to have figured everything out it out or to be in complete control. So many executives truly believe that they have implemented a strong vision, a higher purpose, and a values system. However, as soon as people leave the boardroom, no one knows or cares about it. Indeed, it requires enormous effort to get things together and you must live as you preach. The same goes for coaching towards goals, working across an organization, dealing with the unknown, and celebrating failure as a steppingstone.

From Idea to Success in Idea Generation

The key is to formulate hypotheses for big ideas in problem statements that stem from key drivers and potential scenarios, and then take those and begin testing them in small steps. You will move from a high degree of uncertainty to a lower degree of uncertainty, eventually arriving at projects that can be implemented in a pilot project that brings business results and a scalable solution for a larger implementation. With the right big ideas and hypotheses in place, you can typically test them within 1 to 3 weeks and then iterate two or three times. Then you can start to implement a so-called Minimum Viable Solution (product, process, service, business model, etc.) and learn from the results until you have a proven case with reduced uncertainty.

Typically, MVS is built with very small means and for the sake of testing a concept. In the digital world, it can be done by a digital mock-up, not necessarily the complete logic behind it; service and business models can just be tested after some design thinning and physical products through prototyping tested in the field. Today 3D printing augmented reality, and virtual reality is effective tools to bring into the testing phase.

Last but not least, the most effective instrument ideation is anthropology. To observe to fins ideas and observe to test ideas. It’s really hard to design products by focus groups A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.

— Steve Jobs

If you are interested in learning more about practical business anthropology go to the blog series Do not listen to your customers.

From beginning to end proving commercial potential, can usually be done in 10 weeks. However, this requires the right capabilities, and structure, and strategy for moving from unknown to known. Let´s take a deep dive — because this is HOW to do it.

Deep Dive into the Strategies and Structures for Dealing with the Unknown—Or GET IT DONE

Kotler and Armstrong (2012) define strategic planning as “the process of developing and maintaining a strategic fit between the organization’s goals and capabilities and its changing marketing opportunities.” Planning involves adapting to take advantage of opportunities in the organization’s constantly changing environment (Kotler & Armstrong, 2012). It is clear that the degree of uncertainty, complexity, capability for foresight, and half-life of competence are all dramatically curtailed, while demand and supply are increasingly taking off with scarce resources. The result is a traditional strategist’s worst nightmare. Indeed, five-year plans and huge market surveys are things of the past. Today, it is all about direction and agility, particularly the agility to change, learn, adapt, overcome, and collaborate within value nets. It is essential to acquire, develop, and utilize your capabilities for innovation in a strategic direction and within a context of an ecosystem where value is created such that barriers to entry are decreased, fewer resources are needed, and instability becomes a temporary equilibrium (at least until the next seismic shift). In a nutshell, you can handle uncertainty by turning from denial to acceptance.

According to Penker (2016, 2017), companies and organizations—consciously or unconsciously—develop strategies, leadership, culture, capabilities, and competencies that they use to improve and innovate their business, both internally (e.g., processes) and externally (e.g., value propositions).

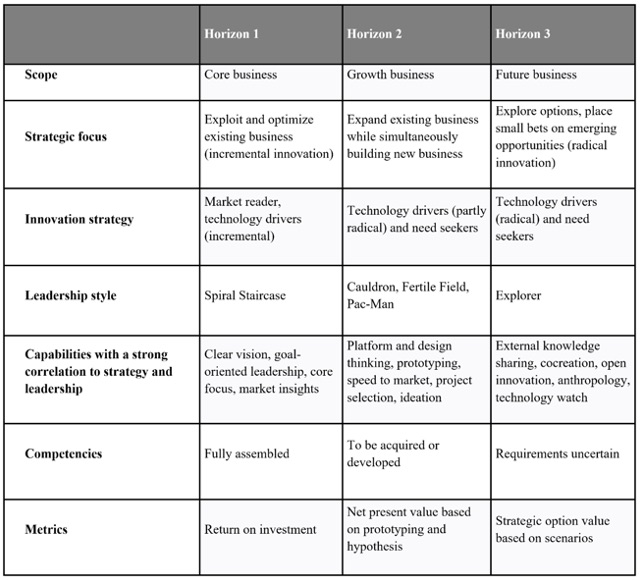

McKinsey’s Steve Coley uses the three horizons to represent parallel innovation activities in terms of overlapping S-curves. We will elaborate upon these concepts further, as they are very important for defining a balanced innovation strategy for sustainable growth and profits:

- Horizon 1 (H1) refers to incremental innovation in the current business. Incremental innovation extends the existing S-curve of an organization.

- Horizon 2 (H2) is about expanding and building new businesses based on more radical innovation, thus forming the company’s next S-curve.

- Horizon 3 (H3) is an explorative approach based on radical innovation to identify and test future possible S-curves, to be commercialized in H2, and ultimately ending in H1.

O’Reilly and Tushman (2004) propose the latent possibility of working ambidextrously[1] with both incremental and radical innovation. Dividing innovation work into different “horizons” in order to manage it effectively is common knowledge in the business world, particularly among C-level executives. Despite this fact, however, many companies still prioritize large H1 projects. The result is numerous projects that frequently create less value for the company than H2 or H3 projects would have.

To counteract this trend, companies can use their common resources optimally to improve and protect their current profit (H1), while simultaneously developing tomorrow’s earnings and market share (H2) and learnings for the future (H3). This would involve using and developing their leadership, culture, capabilities, and competencies most efficiently and, as advised by Scott, killing the “zombie projects” in H1—those projects that “fail to fulfill their promise and yet keep sucking up resources” (Scott, Duncan, & Siren, 2015). To achieve these goals, companies need to understand how to organize and transform themselves into organizations that are able to work in the short-, medium-, and long-term, while maximizing their use of both tangible and intangible resources.

A successful innovation strategy for the unknown is, therefore, based on the fact that the three horizons call for different strategies, leadership styles, capabilities, competencies, and metrics, as indicated by the correlations in the data studied by Penker (2016) and shown in Table 1.[2]

The Innovation360 Ideation Generation process

Table 1: Horizon characteristics. Based on work between 2008 and 2016 by Penker, Ohr, and McFarthing (2013); Jaruzelski and Dehoff (2010); and Loewe, Williamson, and Wood (2001). All data are collected and analyzed in InnoSurvey (2016).

Horizon 1. Most companies put as much as 99 percent of their core efforts into H1, using the incremental/spiral staircase leadership style described earlier. Leaders work step-by-step toward well-defined goals, calculating ROI and predicting the future. Capabilities typically important for Horizon 1 include clear vision, goal-oriented leadership, coaching around goal setting, building of the organization’s core, and insights into the market.

Horizon 2. This strategy is based on anticipating market needs and utilizing technology in new ways, instead of reading the market and responding to it. Crucial capabilities are platform and design thinking, user research, prototyping, ideation, project selection, and speed. The H2 leadership styles are entrepreneurial: challenging the business model, also called Cauldron style[1]; seed-funding external innovation projects and then buying them back, called Pac-Man[2]; and acting as a gardener, keeping what works while removing what does not, called Fertile Field. H2 projects are measurable to the extent that managers work with small experiments and prototypes in order to build the base for cash-flow assumptions.

Horizon 3 is explorative in style, investigating needs on a deeper level and employing new technologies for disruption. In order to sharpen future possibilities through external knowledge sharing, open innovation and co-creation become essential. A common management style includes seed-funding external innovation projects and then buying them back, also called Explorer. H3 projects cannot be measured by traditional methods such as ROI; rather, they are about exploration and learning.

Analysis of these strategic horizons should be based on both external and internal information, which can include quantitative and qualitative data. In this type of analytical process—dependent upon the company’s strategic direction, external context (opportunities and threats), and internal context (strengths and weaknesses)—you can identify what’s blocking forward strategic motion and what could be done to amplify it, either alone or in the collective efforts that form ecosystems. The resultant understanding of the context and strategic direction forms the basis for solutions that can:

- Remove blockages that are hindering or slowing down movement in the strategic direction. These are typically misalignments or lack of capabilities needed for a given leadership style or innovation strategy.

- Amplify the strategic direction. One typical approach of this kind is to identify and initiate more innovation projects in the third horizon to support the second and first horizons. To do so, you can engage the people in specific places in the organization who have the proper leadership and capabilities to execute this approach (as identified in your data analysis).

Thereafter, options should be outlined based on external and internal analyses, alignments, benchmarks, correlations, and initial plans for removing blockages and amplifying the strategic direction of the organization. Typically, recommendations are based on one of three approaches:

- Best Fit, which is based on the current situation and what’s possible without any major changes. This approach is typically based on current conscious strategy, leadership style, type of innovation, and the capabilities and competences that need to be strengthened.

- Best in Class, which is based on the best companies that have the same strategic intent you aim for. These recommendations focus on the changes needed in strategy, leadership styles, type of innovation, personas (the culture), capabilities, and competencies.

- Resource-Based View, which is based on the company’s current capabilities, personas, and competencies. This view focuses on the realistically possible and that the ways in which it can be aligned with the company’s existing overall strategic direction by elaborating on innovation strategy, leadership styles, and type of innovation.

To sum up; Explore the unknown balance with continuous improvements of the known, optimize the utilization of your resources for strategic fix and sustainable growth, meaning doing more with less. This way, you can, with fewer resources, less waste, less time generating more value for all stakeholders from your client and customers to planet earth and our shared future. To get here you need to understand the changing context and your strength and weaknesses in terms of blockers to be removed, amplifiers to be used and alignments around the strategic fit. This is where the Innovation 360 Assessment InnoSurvey® is unique and the logical starting point – to x-ray your organization for strategic fit and change.

—

[1] According to O’Reilly and Tushman (2004), this is the ability to simultaneously pursue both incremental and discontinuous innovation, from hosting multiple contradictory structures, processes, and cultures within the same firm.

[2] The data structure in the InnoSurvey is based on the Innovation360 Framework and is divided into the categories of Why (strategy), What (type of innovation), and How (66 capabilities, 4 process steps, and 10 personas).

[3] An entrepreneurial style where the business model is frequently challenged (defined by Loewe, Williamson, & Wood, 2001).

[4] A style where you invent, outsource, and finance start-ups (defined by Loewe, Williamson, & Wood, 2001).