The Dr Winterkorn Paradox

To be clear on goals is normally a very good thing, to have high expectations is normally a very good thing and to be visionary and challenging are also normally a very good thing. Nevertheless, when you do not align your strategy and goals with the present (and future) capabilities, the company will fail, like VW and pollution tests. It will simply not be possible to reach the goals with the present capabilities, strategy and leadership style. However, VW’s leadership style with some adjustments to its innovation capabilities, some small strategic adjustments and a clear vison in the organisation, would most likely have turned VW into the worst competitor to Tesla. Instead of going for world dominance, cost savings (read ocean) and driving the organisation over the edge by lowering pollution limits to keep its market position, it would most likely have been a better idea to utilize and build on each of its brands and the organisation’s capabilities, defining a blue ocean with the same determination and goal-oriented leadership applied for the red ocean strategy. One could argue that it would be hard to justify jeopardising the company’s position by experimenting, but experimenting and having an inspiring vision most likely did not put VW into the position it is in today, where only the future will be the judge and the whole company is in doubt.

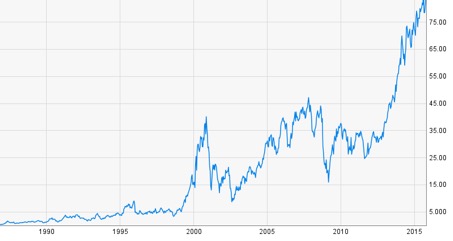

Statistically, based on InnoSurvey™, organisations with headquarters in Switzerland, Germany, Israel, Scandinavia, South Africa and North America, are goal oriented and apply the staircase leadership style, as it is called in the innovation management literature. However, it is clear in our data that the top innovators applying staircase leadership also have a strong vision with an enrolled organisation delivering on it. The organisations with the strongest implementation of their vision, according to our data, have HQs in Brazil, Canada and Turkey but they do not have the most goal-oriented leadership.

Our data shows that goal-oriented leadership and enrolling for a vision do not always go hand in hand, but when they do, this is an efficient way of challenging for innovation and staying on top, if the organisation, at the same time, identifies, develops and utilises its inherited capabilities and DNA (= aligning strategies with leadership, culture and capabilities).